Britons, who are already dealing with the highest rise in food prices since 1977, may have to prepare for fresh vegetable shortages as rising costs and unpredictable weather hit domestic production.

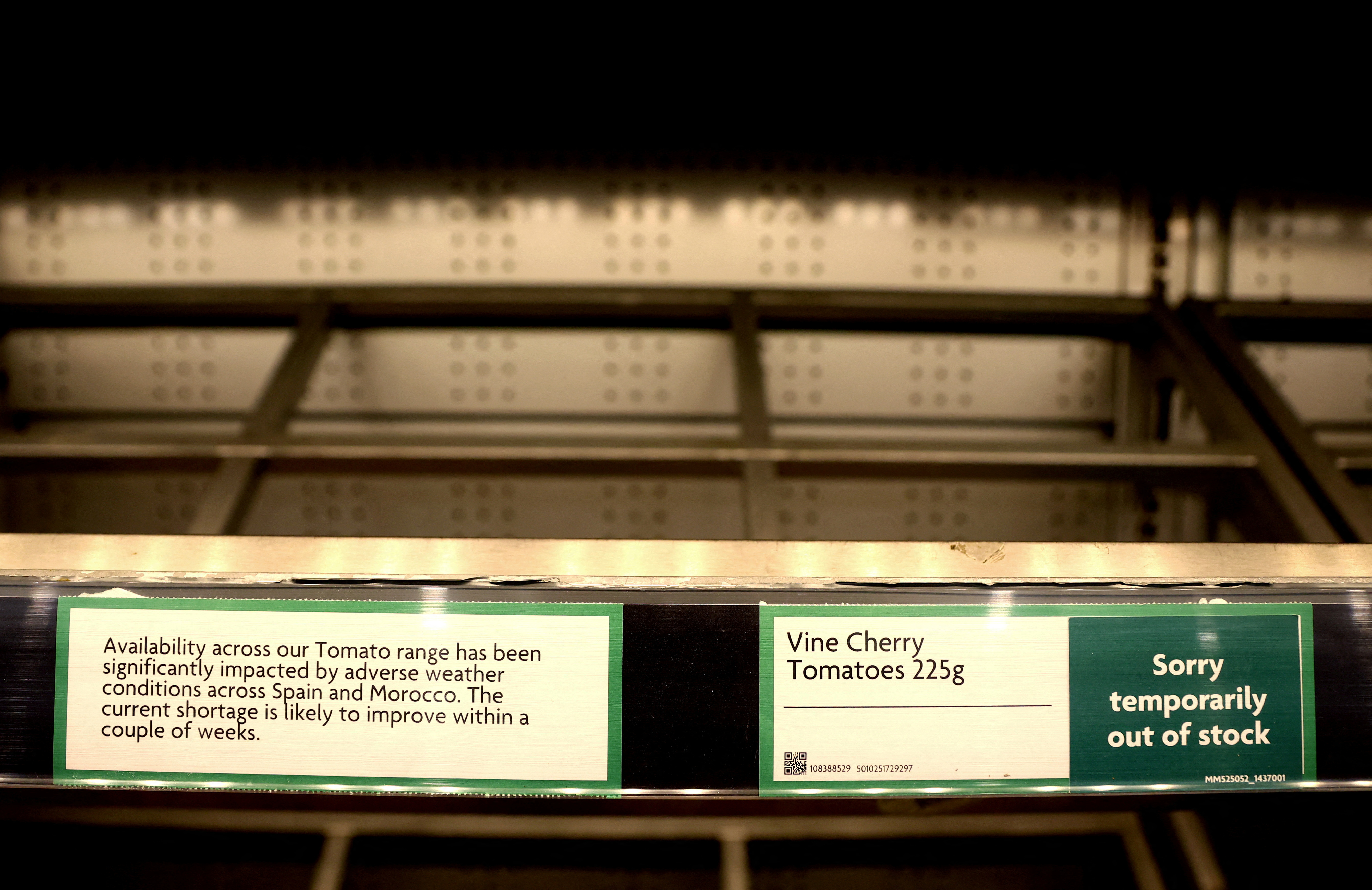

In recent weeks, British shoppers have faced a shortage of tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers due to disrupted harvests in North Africa, while inflation forced industry buyers to spend more on less from key markets such as Spain.

According to tax office data, Britain imported 266,273 tonnes of vegetables in January 2023, the lowest amount for any January since 2010, when the population was approximately 7% lower than it is now.

To make matters worse, UK production of salad ingredients is expected to hit a record low this year as high energy costs discourage British farmers from planting crops in greenhouses.

The tight conditions have contributed to British food price inflation reaching levels not seen in nearly 50 years.

Market researcher Kantar reported on Tuesday that UK grocery price inflation hit a record 17.5% in the four weeks to March 19, emphasizing the problem for policymakers.

Many UK food retailers are buying less because they know their customers cannot afford to spend as much, causing their profits to suffer.

According to Jack Ward, CEO of the British Growers Association, the future of Britain’s fresh food producers is now in doubt.

“There’s a limit to how long growers can continue to produce things at a loss,” he said.

Due to summer drought and winter frosts, growers, farming unions, and shop owners predict more shortages, which could soon spread to other homegrown crops such as leeks, cauliflowers, and carrots.

In March, the UK typically imports approximately 95% of its tomatoes, but this drops to 40% from June to September.

The warnings come after supermarkets were forced to ration egg sales late last year, and cost pressures have spread to poultry and pig farmers, prompting many to leave the industry.

Apple and pear growers have also expressed concern that not enough trees are being planted to sustain orchards.

While the government and supermarkets claim to be confident about supply, the salad crisis has highlighted the precarious state of the UK’s fresh produce industry.

Lee Stiles, secretary of the Lea Valley Growers Association, whose members produce roughly three-quarters of Britain’s cucumber and sweet pepper crop, said that by March, about half of the membership had yet to plant, and 10% had gone out of business.

‘EMPTY SHELVES’

“There are real risks that empty shelves will become more common,” National Farmers Union President Minette Batters said.

The union had warned for months about the dangers of excluding horticulture from a government scheme that helps companies struggling with energy costs, predicting that by 2023, UK production of salad ingredients will be at its lowest level since records began in 1985.

Ward stated that fresh produce margins are typically around 1-2%, but have turned negative this year due to high energy, fuel, and labor costs.

Many retailers’ ability to avoid shortages will be determined by their ability to source produce from other countries.

This is complicated by UK supermarkets’ practice of setting season-long prices, whereas European Union competitors are more flexible, according to one grower who also imports and packs goods.

Britain’s exit from the EU has also played a role, with increased paperwork discouraging drivers from traveling to the UK, which may explain why supermarket shelves in continental Europe remain generally well stocked.

According to Andrew Opie, director of food and sustainability at the British Retail Consortium, which represents the major food retailers, supermarkets are confident in the resilience of food supply chains, especially with the UK growing season approaching.

Smaller retailers, on the other hand, are under pressure.

Engin Ozcelik, a former industry buyer who now runs a food store in North London and consults for others, said they were buying less produce after tomatoes on the vine increased from a typical price of 7 pounds ($8.59) per box to 25 pounds per box.

He claimed that shoppers who used to limit their spending in the final week before payday was now doing so by the middle of the month.

The grower, who did not want to be identified, told Reuters that there was too much emphasis on food inflation and not enough on the overall system’s strength.

“However, if there is no product on the shelf, inflation is meaningless. We must learn from this.”

($1 = 0.8150 pounds)